Part 1

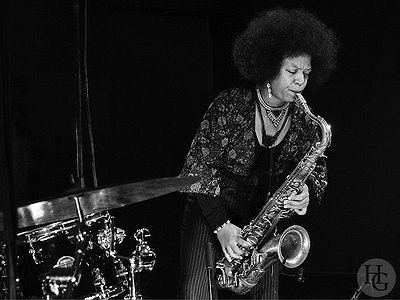

Name: Sakina Abdou

Nationality: French

Occupation: Saxophonist, flutist, improviser

Current release: Sakina Abdou's Goodbye Ground is out via Relative Pitch.

If you enjoyed this interview with Sakina Abdou and would like to know more about her music, visit her on Instagram, and Facebook.

When did you first start getting interested in musical improvisation?

My first encounter with music, including improvisation, was as a child. I didn't know the difference between written and improvised music at the time (I'm not sure we still need to). I was a baby, living in a house where one of the rooms was dedicated to listening to high quality music on a Voix du Théâtre speaker system by Altec because my father was an audiophile.

For me it was a meeting with sound as a material, as a space and as an "address". My father's dream at the time was to be able to close his eyes and find himself in the room in which the record was recorded, to be able to indicate where each musician was placed and the exact space that separated them from the microphone. From that moment, I was more sensitive to this "living" dimension of the music than to its improvised, or not, characteristics.

I listened to a lot of West African music, jazz, world music ...

How to delimit the part of improvisation and writing in traditional music?

History and collective memory are also a form of writing in a way. And anyone who lends their blood to revive history and memory, brings it to life again, with the improvisational characteristic that always runs alongside it, at least in one place. There are many ways of conceiving improvisation and writing. Music, even if it is improvised at a given moment, becomes a form of writing as soon as it is recorded and engraved on a record.

Later, my first encounter with live improvised music was in 1998 with the Zoone Libre collective when I was 13/14 years old. At that time, I attended my first concerts that gave prominence to improvisation, in particular with the group "Zig Zag" (unfortunately no record was made). These are very good memories. I was the hairdresser, the make-up artist and my mother, who was the lighting director, allowed me to skip school to attend the concerts. I was astonished at so much strength and freedom.

I joined the collective right away and participated in my first artistic projects, independent of any school curriculum. It was all about creating new music in which I saw improvisation and writing being built and recomposed from the inside and by several people together. The practice of improvisation was approached in a completely open way.

I would, much later, make my first recording with one of the formations of this collective: Vazytouille.

Which artists, approaches, albums or performances involving prominent use of improvisation captured your imagination in the beginning?

One thing lead to another, I became interested in the projects of other members and friends of the collective, much older than me and already well established in the improvised music scene in the North of France, notably Christian Pruvost, Michaël Pottier and Laurent Rigaut.

This is how I discovered the venue "La Malterie" (10 minutes by foot from my home, it was very convenient!) as well as the collective of improvisation and experimental music "le CRIME" (one of the two former entities of the current "Muzzix"). It was very radical and uncompromising music. I was in the front row of the crazy, joyful and brutal energy of the improvisation orchestra "La Pieuvre" led at that time by Olivier Benoit.

A few years later, I joined the collective via this orchestra. One of the strongest artistic experiences of my life (including from the sound point of view, if one day I have tinnitus, this is the reason why for sure!) I quickly learned the circular breathing technique as an instinct of survival. I remember a concert at the Météo festival where we stayed frozen for almost 20 minutes on a single note held with the wind section. The saliva began to flow from the corners of the mouth, the muscles to stiffen and freeze ... It was intense physical practices with often the eagerness and rage to go far, to seek the end of our own limits individually and collectively.

I immediately realized how lucky I was to be able to live these rich artistic and human experiences which were of an extraordinary order. It is from there that I started to arouse my curiosity and to listen to random records in the media library.

Focusing on improvisation can be an incisive transition. Aside from musical considerations, there can also be personal motivations for looking for alternatives. Was this the case for you, and if so, in which way?

I have always had the impression that I was born a bit sideways. For a long time, I discovered and learned languages that seemed as foreign as they were familiar. One foot in, one foot out of the aesthetic delimitations proposed to me by the frames I met at school and in music venues.

I leaned towards these languages in a process of appropriation. Nevertheless I had the feeling that I might be able to find myself partially but never fully. Through non-idiomatic free improvisation, I understood that the field had no boundaries and that it was up to me to cultivate myself in whole and no longer in parts. It corresponds to a moment in my life when I wished to stop looking for myself elsewhere and "cultivate" my language without feeling the need to "adopt" it.

Improvising is creating with what you are and what you have, without feeling like you are missing out. It is also about feeling the legitimacy of expressing oneself without waiting for someone to give us their approval.

For a long time, I took several different, long artistic courses. It was by curiosity as much as by enjoyment, but perhaps also to try to "be part of" current trends, to reassure myself by trying to gain a feeling of legitimacy to be "plural". At the time, not being well aligned with the established framework was not much valued.

Without going as far as to claim that I suffered for it, at least I feel like I had to work harder to gain professional legitimacy to follow my own path. And the path of improvisation gradually became a central path into which all my artistic experiences could flow.

What, would you say, are the key ideas behind your approach to improvisation? Do you see yourself as part of a tradition or historic lineage?

I must have a little problem with identification ... Maybe because I am a woman and as a child I never met an all inclusive "model" that I could unconsciously walk into, imitate or copy as a "character". It was difficult for me to "reformulate" myself through screens as was often expected.

With the instrument it's the same. I love the sax but I never "idolized" the instrument to the point of only listening to saxophonists. I'm not very "gear orientated” either ... I listened a lot to music in a broad, general and abstract way. At the time, I was doing the readings, I liked to read the piano, the flute or the trumpet, and basically I didn't have a great attraction for the clichés and patterns of the sax. I lived this little "disorder" of filiation with as much solitude as freedom.

For a long time, I was in a sort of exquisite corpse, a pick and mix of artistic references, a sort of sweet and salty tajine of different cultural references that I had trouble digesting ... At 18, I remember going to an examn of early music dressed in a boubou. For sure, the jury must have been quite surprised!

With time and the development of my improvisation practice, I can now say that if I had to cling to a lineage, it would rather be that of free jazz. Among other things, the music it has produced touches me. As in early music, I am sensitive to its eloquence, its breath, its exuberance, the suppleness of its features and the radicality of its contrasts. Because many of the people who took me under their wings, both humanly and artistically, the "big brothers" with whom I learned improvisation in an almost "family" setting, went through this in their youth, I have the impression of inheriting it and of being partly shaped by it.

I also feel connected to this approach of music which, at the time, aimed to push the boundaries of a framework that felt too narrow to allow the full extent of expression to go wild. Personally, if I try to break something, it is not the language itself, it is its limits. I don't try to break the codes at all costs as a posture, to go against the foundations by principle.

Sometimes I play in an enraged way, but I also aspire to cultivate appeasement, because with time I am wary of any posture that will eventually alienate, stiffen and exhaust itself in its own caricature. I love to break with playing, but sometimes I prefer to erase, and other times to stretch just a little. Sometimes with force and brutality, sometimes with flexibility and softness. What matters to me is what these gestures open up and make the expression germinate.

Even if I also take great pleasure in working within restrictive frameworks and putting myself at the service of other people's music, I am looking for this movement and flexibility. If I have something radical in me, it is perhaps in this spot that I try to push in a transverse way through the aesthetics and the languages. An inclusive music more than a contesting.

The times we are living in are not exactly marked by an uprising of freedom and I have the feeling that the trend is more inclined to the alienation than to the liberation of the people. My parents would have liked to push the revolution forward but they were broken in their mind and their bodies. I inherited that aspiration but also a generation of disillusionment later. I still try to find what I can grow with these crumbs.

What was your own learning curve / creative development like when it comes to improvisation - what were challenges and breakthroughs?

After earning my spurs in music institutions, the first challenge was about accepting to start again from scratch with a feeling of legitimacy, of the kind of recognition that society pushes us to seek. As far as I am concerned, it was the moment when I started studying a different instrument (the saxophone) while I was finishing my flute course at the conservatory at the time when other students were looking to specialize by attending a high Conservatory like Paris, Lyon or Brussels.

And then, the moment when I felt like I had to reinvent my brain to start studying jazz and harmonic grids after completing a classical saxophone course. In these moments, you find yourself in a position of fragility and exposure in bright daylight. Your conscience is sharp enough to sense your "awkwardness" and your pride is inflated enough to demand excellence as a starting point.

So I would say that my first breakthrough was the first time I decided to take on the responsibility of playing a lousy chorus on a blues when I was already a double gold medalist in classical saxophone and early music. That time I felt quite proud to have taken the chains off and from then on I could start learning.

As for improvised music, it is a field that I have always cultivated in parallel to any form of music education as a release. My first improvised project as co-leader, the saxophone duo with Jean-Baptiste Rubin «Bi-Ki?» was a very determining experience to help me to begin to search my own way of creating music.

My challenge as well as my breakthrough in the large area of improvised music was to unlock the principle of communicating vessels, despite others' mistrust of others and despite the imperatives of radicality or consensuality required according to different heritages, and methods of good conduct which might have been in place.

From then on (not so long ago!), I began to discover the sensation of inventing and creating. In all humility. At least to invent me and not to "reformulate" myself within these frameworks. In practice, this translates to more appropriation in my approach to my practice time and more spontaneity and confidence in my play time. It's the balance that allows me to sow seeds where I decide to, and to have enough availability to see them blossom where I don't expect them.

Tell me about your instrument and/or tools, please. How would you describe the relationship with it? What are its most important qualities and how do they influence the musical results and your own performance?

What strikes me in the saxophone (as in the flute) is its connivance and complicity with the voice, the word. I like the relaxation and the precision of the body that one can tame through it as well as the great widening of dynamics and distancing that it allows with regard to the breath, the sound, the voice.

Whether it's about sound, rhythm or harmony, I like to work on very precise things for hours on end on the one hand - and to disconnect my consciousness and lose control at other times. I finally understood, thanks to a friend’s advice, that you never create “nonsense" when improvising and I realized that you’re just keeping your knowledge on a leash. If it seems difficult to play freely and without constraints, it is because the leash is not positioned in the right direction.

I like my instrument because of its tessitura, its flexibility in terms of the sound and the digitality allowing me to position myself on the edge of a technical nature, forgetting what I want to say, and of a spontaneous expression, forgetting what I want to do.

This tipping point is magic to me. You cannot tell if the musicality that comes out of it is from yourself, your heritage or the cosmos. I find it fascinating.