Part 3

How, do you feel, could contemporary compositions reach the attention of a wider audience?

Perhaps by not marketing them as “contemporary compositions!” Labels such as “serious music” and “art music” have unnecessarily isolated work that could potentially be enjoyed by a much broader audience. Thankfully, these categories are dissolving before our eyes every day. I can’t count the number of genre-crossovers I’ve seen in the last few years. Musicians who have been known for their rock or pop work have written music commissioned by orchestras and chamber ensembles and opera houses. Likewise, composers more commonly working with those sorts of organizations have written albums with a rock or pop orientation and have worked with bands. I’m not able to do justice here to the subtle stylistic hybridizations that are happening in this music, of course. It’s getting increasingly difficult to find succinct descriptions of both the artists and the music they’re making. I can only see that as a good and exciting development.

Music-sharing sites and -blogs as well as a flood of releases in general are presenting both listeners and artists with challenging questions. What's your view on the value of music today? In what way does the abundance of music change our perception of it?

I find the abundance of music today overwhelming and hard to keep up with, exhausting but thrilling. Everyone who wants to seems to be able to make music and that’s probably a good thing. I have heard people worry that this phenomenon of widespread music-making, facilitated by user-friendly software applications, will degrade standards and result in poorer music in general. I don’t buy it. Bad music can be written just as easily with a quill pen in soprano clef.

Last semester at Duke, I taught an undergraduate composition seminar for students who had never written anything before. Some of these students couldn’t read music at the beginning of the class. What I found was that they all had passionate, fascinatingly divergent ideas about what makes good music. This was because they were all voracious consumers of music. They had developed tastes. The music they wrote surprised and invigorated me, and I wasn’t alone. The excellent group yMusic graciously gave us a reading/recording session for the students’ final compositions. yMusic was still talking about how much they enjoyed working with these first-time composers when I saw them recently. So this is my hope for the superabundance of musical activity we’re currently experiencing: that it will yield unexpected and exciting new directions for music.

Composers have traditionally found it hard to secure a living with their art. What are the financial realities you're living with and in which way, do you feel, could they be improved?

No composer who is struggling financially wants to hear advice from someone like me, I’m sure. I was lucky enough to secure an academic job right after grad school—and I do believe that luck had something to do with it—while so many other qualified people spend year after year on the job market. It’s heartbreaking.

But since you ask: in addition to the traditional academic/institutional trajectory, I think we need to imagine new contexts for composers to work in. One way to do this is to think about collaborative contexts in which composers could make important contributions. I’m not talking about artistic collaboration but rather entrepreneurial collaboration. Composers are very good at managing lots of small details; they have excellent abstract thinking skills; they know how to temper complexity with clarity; they have hands-on experience challenging others to new heights of performance (literally.) They also have an intimate understanding of the business of making music, if not always the “music business,” per se. That means they have discipline and practice long-range thinking. These are useful and marketable skills. Startups could benefit from having composers on board. If composers currently find it hard to find these ventures or to market themselves as startup-friendly or to create their own entrepreneurial projects, perhaps we should start giving them the tools and opportunities to do this while they’re still in school.

At Duke, I’ve created an undergraduate arts entrepreneurship course in partnership with the Fuqua School of Business that brings together students from a variety of backgrounds—visual arts, dance, computer science, engineering, history, neuroscience, music, economics—who share a common interest in the arts. Together these diverse teams develop entrepreneurial projects in an arts-related field and launch them in the market by the end of the semester. Composers would fit right in to these groups.

Usually, it is considered that it is the job of the composer to win over an audience. But listening is also an active, rather than just a passive process. How do you see the role of the listener in the musical communication process?

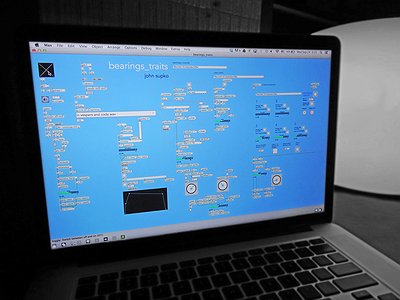

I like to say that I am my first listener. If I’m interested by what I hear, there’s a chance others will be, too. The generative process allows me to work as a listener listens, using my reactions to the computer’s unpredictable interventions as a way to decide how to develop material.

Find out more about John Supko on his website.