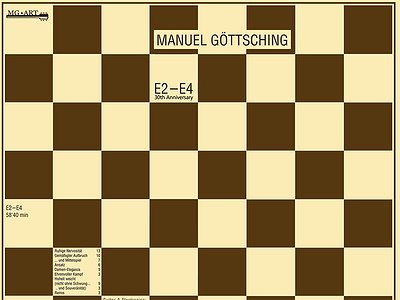

Artist: Manuel Göttsching

Nationality: German

Occupation: Guitarist, composer, producer

Album: E2-E4.

Originally released in: 1984

If this review of Manuel Göttsching's E2-E4 piqued your interest, you can obtain a copy at the offcial Ashra store.

After having finished an extensive 16-date tour with Klaus Schulze, Manuel Göttsching was in great shape and spirits and in a creative mood. On the evening of December 12th 1981, he sat down in his Berlin studio to toy around with all the instruments and equipment he had collected over the years. This was to be one more concert, a private one, just for himself and his own music.

For the 13th, he and Schulze had decided to attend a performance by experimental musician and drummer Klaus Krieger, who had earlier played with Iggy Pop and Tangerine Dream, in Hamburg. Schulze lived in Hambühren, Lower Saxony, whereas Göttsching still had his homebase in Berlin, so they had to take the trip separately. Part of the idea of the session was to dub the music to tape, to have something to listen to on his walkman during the flight.

But when he wrapped things up for the night, he suddenly had a "finished, faultless recording" in front of him. As he realised, “it was certainly playing around but pretty damn good playing around.”

More than 40 years later, that assessment still stands. E2-E4 is rightly considered one of the cornerstones of contemporary music, a pioneering effort for the electronics scene and a proud personal achievement for Göttsching. It is also an album that changed the way I think about music.

~

It is probably one of the hallmarks of a classic that you can instantly connect certain cliches and stories with it. This is certainly true for E2-E4, which has by now been dissected, discussed, analysed and written about so much that the album has all but overshadowed the excellent body of work that Göttsching has built up outside of it.

Some of these anecdotes include that Star Wars robot R2D2 influenced the title. That the idea for a piece by the name of E2-E4 had been on Göttsching's mind for a while and that he had merely been looking for music to match the title. That E2-E4 was propelled into the limelight on the strength of it being played in underground clubs and the release of various unofficial house edits until "Sueño Latino", which boiled the one-hour-long piece down to a ten-minute dancefloor filler, paved the way for its global appreciation.

The story of how the album remained in limbo for three years adds to its allure. When Göttsching and Schulze had met for that Krieger performance in Hamburg, Göttsching had already played his friend a few minutes of the music and Schulze had liked it. Manuel visited Richard Branson, who had signed him with Virgin, in London. After playing him the music, Branson, whose baby peacefully fell asleep to it, claimed that it could make him a fortune. However, Branson was no longer responsible for Virgin Music and Göttsching did not trust anyone at his record company to be remotely interested in the piece.

There were also "practical" reasons which made a release difficult to say the least. As Göttsching remembers: “At this time, all major album releases still took place on vinyl. 20 minutes per side were considered the limit and pressing plants and labels would routinely reject a work if it exceeded that – or accept it with reluctance only – because it compromised dynamics. Clearly, these were not exactly the best preconditions for 60 minutes of E2-E4.“

And so, the tape went “into the drawer” for a while.

In 1984, Schulze, after selling of his first label Innovative Communication (which, coincidentally, had also published two albums by Klaus Krieger in 1981 and -82), was getting ready to launch his second imprint Inteam, and asked Manuel if he had anything to release. Göttsching reminded him of the tape and so, E2-E4 became the fourth catalogue entry on Inteam. Still, the total running time had to be cut by 5 minutes between the two sides - the full piece would only become available a few years later, on CD. Few in Germany thought much of it at first and a local newspaper actually berated it for being backwards-thinking.

Today, copies of that initial print run routinely fetch up to 150-200 Euros.

~

What makes this record special and unique, in my opinion, is not the fact that it was recorded in a single session – although it does offer very interesting insights into the balance between the “perfection” of a single inspired moment versus the “perfection” of endless studio sculpting. To me, E2-E4 opened up an entirely new way of thinking about building a piece, an approach that would become a hallmark of electronic club music.

Of course, this album is based on improvisation, just as earlier Ashra Tempel and Ashra releases had been. Those, however, had been edited, spliced together and composed at the mixing desk. Here, Göttsching takes the plunge and records himself in real time. And yet, this is in no way jazz, not even in the sense of Coltrane's Africa Brass, whose modal magic had once so deeply impressed composer Steve Reich, who in turn had kindled a sense of kinship in Göttsching.

The virtuosity at play here owes nothing to speed, manual dexterity or physically impressive extended techniques. It is through ever so slight sonic and timbral variations that Göttsching propels the music forward – the themes don't change, their colours do, as do the relations between them. It is a game with perception that dissolves the questioning mind:

The more you listen, the more you understand, yet the more you understand, the more you question what it actually is you're hearing.

~

And then there's the magic that happens at precisely the halfway-mark. Göttsching could have easily ended the music here. Even without what follows, E2-E4 would have gained its place in music history.

Instead, he plugs in his guitar and allows it to soar on top of the groove for another thirty minutes. It is a surprising moment, a break within a seamless movement. But it quickly passes and suddenly gives way to an even wider space – one in which anything could happen.

Now he has drawn everything out of his machines, he can now leave them playing by themselves for the remainder of the time. The groove becomes trance-like in its unflinching repetitions, while the focus now moves to the melodic facets of the piece, to the human side of things.

It is almost as if Göttsching wanted, after all but disappearing behind his electronic patterns for the first half, wanted to reveal himself and step to the fore. Unlike Kraftwerk, who had the outspoken desire to make themselves redundant, the artist never loses his humanness here. It is a magical moment and testimony to a way of thinking about the man-machine continuum that has rarely been attempted since.

~

Of course, the historical perspective has always been that E2-E4 served as a blueprint for techno and house and that claim is certainly not without its merits.

And yet, it still intrigues me that, when you take a closer listen, the piece doesn't actually have a continuous kick drum. Instead, Göttsching leaves out the fourth pulse of every beat, a simple act of omission, which awards the rhythm a deeply melancholic twist: Contrary to the endless “four to the floor” bass drum, on E2-E4, every bar of music suggests the music, just like our lives, could end at any moment.

Göttsching keeps the flame burning for as long as he is able to, but even he can't avert the inevitable. And so, for exactly 59 minutes and 34 seconds, everything stays suspended in an infinite space between one reality and the next until shapes dissolve again, silence returns and it is finally time to say goodbye.