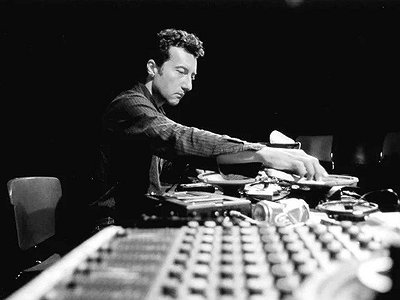

Name: Lionel Marchetti

Occupation: Composer, sound artist

Nationality: French

Recent release: Lionel Marchetti teams up with Australian chamber ensemble Decibel for Inland Lake (Le lac intérieur), out now via Room40.

Over the course of his career, Lionel Marchetti has worked with a wide range of artists, including Jérôme Noetinger, Jean-Luc Guionnet, Cat Hope, and Vanessa Rossetto.

[Read our Jean-Luc Guionnet interview]

[Read our Cat Hope interview]

[Read our Vanessa Rossetto interview]

[Read our Jérôme Noetinger interview about the Revox B77]

For an even deeper look into his thoughts on music, read our earlier Lionel Marchetti interview.

The question that arises for me in any art (and particularly in an art like musique concrète, only permitted by the use of recording machines) is the following: is it simply a question of saying something, of only expressing oneself (I insist here on the pejorative side of this expression)? Or rather, to take advantage of it - in the sense of seeking to densify one's life, to increase one's sense of the world - to finally move around, change territory, forget oneself, finally survey what the poet-thinker Kenneth White calls a “new territory of being”? And all this by sharing it, of course, through a completed work.

One thing is certain: the tool, whatever it is, profoundly modifies our vision of the world. Well sharpened, the tool cuts through easy, formatted layouts. It can help us envision the path, to walk another path. To discover something else. Finely used, it is the stylus that both draws a map, and at the same time, asks us to fold it, to put it in our pocket to come closer to what is real from now on with our entire body. Or rather: to come closer to the real again.

In my discipline, definitely made possible by and intrinsically linked to electroacoustic techniques, I work with a multiplicity of tools. All of them are linked to each other, from outside microphone recordings to loudspeaker listening, passing by a craftsmanship of electricity that includes both synthesizers and musical computers and the multiplicity of peripheral machines, all dedicated to recorded sound given back to the space with loudspeakers.

For me, the entire electroacoustic chain is a large complex tool intended for working on the strength of the sound image. Technology is a manifesting energy, and you have to dance with it. Technology makes it possible to open up a field, a breath, territories, to approach the most open poetics possible, the very one which, as, to quote Kenneth White again, is situated between concrete and abstract, on a crest line, beyond a ready-made answer - beyond any formula that would paralyze the whole thing and render the work stillborn.

It is a question, for me, of approaching a force of image which will have to keep below an invisible, inaudible vitality and which, at the same time, will have to take the path of the listener's ear to go to the point of telling him - offering him - that the space is free. Beyond what we imagine: where there is an essential breathing, specific to each one, specific to each one.

This is how the quality of the studio, in terms of the silence it offers, the way in which it will offer a space of contemplation for the composer and this, well beyond the technical equipment, has a fundamental influence on the rendering of compositions, even on their very poetics.

I worked in many different studios. These include, on the one extreme, the home studio on a corner of a table in my student attic, often in the evening, with just a K7 turntable, a CD player, a camera microphone, and an old Revox A77 in my hand. By composing Kitnabudja Town, for example, even though every day I was composing, opposite, at CFMI in Lyon (at Lyon 2 University) Microclimat, Sirrus, L'incandescence de l'étoile in a studio that was once frequented by students and equipped with professional JBL loudspeakers, a magnificent 16-track mixer, various synthesizers, a sampler, and already a computer to manage the various connections!

But also, quite differently on the other end of the spectrum, working in large silent studios like those of Ina-Grm in Paris, for La grande vallée or Portrait d'un glacier (Alps, 2173 m), Equus (large vehicle), or even the Gmvl cellars in Lyon with their exceptional Cabasse enclosures, for Mue (the brilliant residence) and Chasser (first natural study) ...

Always, the music that was composed in these places - these spaces - was absolutely different, and it also became absolutely other; they were found charged with their own poetics—sometimes, moreover, to my great surprise!—; music strongly influenced, therefore, by the various qualities of the place, even though many recordings and necessary sound filming had been made outside.

I would never have been able to compose La grande vallée anywhere other than at the Grm, just as the Red Dust triptych remains absolutely linked to the smallness of a small home studio and its tiny loudspeakers. Noord Five Atlantica is linked to the former Césaré studios in Reims where Christian Sébille had installed incredible loudspeakers, gigantic, whose name I forget, with a woody taste and embedded between the mixing desks and other synthesizers: I had the impression, in this place, of holding the bar of a supertanker on an ocean with black and volcanic water!

My current studio, with its 20 mismatched loudspeakers, on which glass domes are balanced, suggested to me some studies of concrete music with fragile craftsmanship!

Of course, the composer of concrete music can go outside, on the ground, record their sounds and thus draw inspiration from the great outdoors. It is fundamental for me, too. The outside is my breath. But once in the studio, the particular breath of it will change everything and breathe new forces, new writing directions; all associated, of course, with my personal life and the complexity of any life journey ...

Technology, in the art of concrete music, is therefore fundamental and seminal. It is a discipline where we have the chance to mingle with both a constant evolution of tools and with this fixity, for more than a century now, of the way of listening to recorded sounds: faced towards one or more loudspeakers.

In fact, since the invention of recording, nothing has really changed in terms of how recorded sound is received—and that's fortunate. The loudspeaker is to the composer of concrete music what the screen is to the filmmaker. Of course, styles, writings, and aesthetics are constantly changing: relationship to time, durations, forms, poetics, and tools, from analog to digital; obviously, certain qualities change: Pierre Henry's loudspeaker in the ORTF studios is different from those of today—but the fundamental reception of the recorded sound is always identical, the way of receiving the sound via the membrane loudspeaker that collides with the air molecules remains almost identical!