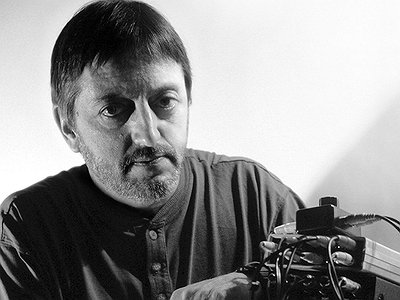

Name: David Lee Myers

Occupation: Sound artist, visual artist

Nationality: American

Current release: David Lee Myers's Xenography is out via Pulsewidth.

If you enjoyed this interview with David Lee Myers and would like to listen to more of his music, visit the homepage of his Pulsewidth label.

Where does the impulse to create something come from for you? What role do often-quoted sources of inspiration like dreams, other forms of art, personal relationships, politics etc play?

There is something I need to hear, and it does not exist. This is easily the greatest motivation for me. Listening to records can be deeply unsatisfying because I rarely have the feeling that I am discovering anything new.

In 1988 I created an electronic system of long delays and other effects with the intent of using it for guitar looping. What actually emerged was completely unanticipated: the first “Feedback Machine.” This became the tool with which I could find sounds and forms that were truly unknown to me and which—to my ears and mind—needed to be produced. The initial result was my first album, Engines of Myth.

What I need to hear is beyond dreams, relationships, or politics, perhaps closer to metaphysics.

For you to get started, do there need to be concrete ideas – or what some have called a 'visualisation' of the finished work? What does the balance between planning and chance look like for you?

With my Feedback Music work, the first movements are almost pure chance—by design, as it were. The feedbacking circuits are purposely encouraged to do what they wish, and as sonic activity begins to emerge, I must do my best to steer it into (hopefully) satisfying tones and shapes. In other scenarios, I do have a relatively preconceived vision of where I want to go in an audible or emotional sense.

For example, my Room in a Moon House was guided by the need to investigate a certain emotional space. The package art for that album describes it better than I can in words.

Is there a preparation phase for your process? Do you require your tools to be laid out in a particular way, for example, do you need to do 'research' or create 'early versions'?

Most of my work has been live improvisation, but more and more of late I tend to construct pieces through editing and layering. In such a case I certainly have a lot of preparatory chores—generating sound bits via feedback or other electronics, categorizing and cataloging them, and so on. Then my tools are laid out and I’m ready to start.

I do not go through many different versions of a piece; I am impatient by nature and by the end I would be ready to shoot myself. I may realize that a bit of something needs to be altered along the way but by and large a piece either works, or it goes into the trash bin.

What do you start with? How difficult is that first line of text, the first note? Once you've started, how does the work gradually emerge?

Many times that first movement is simply technical. “What sound might I get if I connect components A, B, and C?” Such a beginning may lead to an entire finished track once the juices (i.e. fevered module patching) get flowing.

Other times, it may be a note or texture heard in an elevator or on the street which suggests a direction. Frog and toad songs inspired an entire album by the legendary electronic composer Tod Dockstader and myself, Pond. Frequently, once the ball gets rolling it’s almost hard to stop.

Perhaps I’m fortunate that way except for the fact that almost too much results, and I find I have a glut of material. Recently I’ve felt the need to expunge hundreds of hours of unreleased recordings from my archive, which I’ve done, holding back enough for a release I titled Cull, for obvious reasons.

Many writers have claimed that as soon as they enter into the process, certain aspects of the narrative are out of their hands. Do you like to keep strict control over the process or is there a sense of following things where they lead you?

I wonder if there is any artist who really “keeps strict control”—this would seem to be more characteristic of mathematicians. Not that I exert no power over what goes on, but as I’ve said elsewhere, my sound works are the result of capture, selection, processing and combination; essentially, I do not “make” sounds, but allow latent or unseen forces and processes to present themselves via simple technologies. I select the methods, set the stage, and as the phenomena emerge I of course introduce my own aesthetic judgements to the mix.

Therefore the sounds which are presented are neither completely random science nor the gesture of an artist’s hand, but something between the two, and I believe this to be the most effective approach toward evoking meaningful impressions of unseen worlds. So my devices and their sounds most decidedly lead me, I wouldn’t have it any other way!

Often, while writing, new ideas and alternative roads will open themselves up, pulling and pushing the creator in a different direction. Does this happen to you, too, and how do you deal with it? What do you do with these ideas?

Fortunately in this regard, I produce quite varied projects. Some albums are nearly ambient, some are highly percussive and rhythmic, others grim and yet others almost humorous.

If, while working in a certain direction, I discover a new and unrelated angle, a piece can be sent off to an appropriate parking spot. In time the track may determine a whole new sonic path to be pursued.

There are many descriptions of the creative state. How would you describe it for you personally? Is there an element of spirituality to what you do?

I might describe myself as a sort of spiritualized research scientist.

My aim is to discover the unknown—unheard sounds, unimagined forms and patterns which originate in electron paths. The world of the electron, in any practical sense, is territory we humans will never be able to touch directly. The electronic musician must navigate in this vaguely perceived world as best as possible, knowing all the while that the forces at play in the universe dwarf him or her.

For me, there is a tangible sense of awe in front of these forces as I attempt to uncover them. An album such as my Ruins attempts to bring these energies to the fore and imagine a more or less natural environment for them.

Especially in the digital age, the writing and production process tends towards the infinite. What marks the end of the process? How do you finish a work?

We all know of musicians who have at one time or another spent years reworking an album. Even the thought of this gives me a headache. If I have collected a number of tracks that work, that work together, create a coherent feeling, and they total around an hour, I am done. End of story.

And I always work with a collection of tracks, an album, in mind. This would seem to go against the current mindset of “songs” being predominant, but so be it (one wonders what Beethoven would have to say to this!)

I was fortunate to work with the great photographer Minor White in the 1970s and he had an interesting take on this subject. Regarding an exhibition or book of his work, he said that the sequence of pieces was at least as important as the pieces themselves. I heartily agree.

Once a piece is finished, how important is it for you to let it lie and evaluate it later on? How much improvement and refinement do you personally allow until you're satisfied with a piece? What does this process look like in practise?

Most of my work has been produced live-to-recording and largely improvised, which results in a lot of recordings! Usually after some light editing I will examine a proposed track many times, envisioning certain changes or additions. My formula is “record once, listen ten times.”

However, that said, it is possible to stomp something to death and one must tread carefully. Once an album is published I can rarely tolerate hearing it again, except for more ambient outings such as Lustre which—at least for my ears—doesn’t get worn out as easily.

What's your take on the role and importance of production, including mixing and mastering for you personally? How involved do you get in this?

Every aspect of a project is essential to me. From an idea in my head to the finished product on the street, I have total control and take complete responsibility for composition, instrumentation, recording, mixing, mastering, artwork and package design / production—this, pertaining to albums on my own label Pulsewidth.

When creating an album for other labels, I get my hands in there as deeply as they feel is acceptable; occasionally we might need to compromise on some aspect of artwork, or the label may insist on mastering, but in no case has this ever substantially altered what I hoped to produce. I would not allow it.

After finishing a piece or album and releasing something into the world, there can be a sense of emptiness. Can you relate to this – and how do you return to the state of creativity after experiencing it?

After an album wraps up, I tend to put it out of my mind and clear my head as thoroughly as possible. As said, in all likelihood I will not hear it again for years, if ever. For a few weeks I will not touch a switch or fader. Perhaps I will do a major reconfiguration of my electronic layout, putting certain devices away and bringing others out of storage.

After a while when the slate is wiped clean, ideas start to come and I can begin experimenting with fresh sounds and shapes.

Creativity can reach many different corners of our lives. Do you personally feel as though writing a piece of music is inherently different from something like making a great cup of coffee? What do you express through music that you couldn't or wouldn't in more 'mundane' tasks?

To slightly paraphrase G.I. Gurdjieff, if you can prepare a cup of coffee consciously, you can do or be anything. However, it may not be at all obvious what a high bar he is setting.

If one were conscious in Gurdjieff’s sense, one would probably have no real need for art. Perhaps in part I create music because I am not yet conscious in this sense. But possibly art may be of assistance on the path.